But the Data!

One of the more reasonable responses to the idea of deconstructing and reconsidering E-C theory is to point to Graves's data.

Point of view: maybe we can just tweak it a bit

From the research project outlined, it should be apparent that the emergent cyclical theory of adult behavior did not arise capriciously, nor is it a product of armchair theorizing. I did not visit the Gods on Olympus, nor have I stood on the mountaintop in Sinai to procure the substance in its words. It came about in an arduous, systematic fashion.

— Clare W. Graves, NEQ p. 51

One of the more reasonable responses to the idea of deconstructing and reconsidering E-C theory is to point to Graves's data. The data were collected over the course of an initial 7-year period, with further data collection and research continuing for more than a decade longer. The results defied Graves's expectations, and he had to rethink assumptions and alter his conception of the theory several times as a result.

Graves's process included a new set of people categorizing the raw data each year, and no matter who did the categorization, the same patterns always emerged. This is so unusual with the sort of free-form data Graves was working with (essays describing the person's own conception of the mature adult human) that Graves initially wondered if he had contaminated his experiment somehow. But as the consistency was maintained year after year, he accepted that there was a real, stable pattern, on which he then based E-C theory.

"How do you account for what Graves found?" Gravesian defenders ask. And they have a point. Graves's data collection methodology seems quite sound, given the limits of its time and place and the complex nature of the topic. A similar process was later formalized (independently) as grounded theory. You can read the essentials of Graves's process on the E-C theory Wikipedia page, and a longer narrative account in two parts on Keith E. Rice's site.

But there's one big problem: The data is long gone.

Wait... no data?

For whatever reason, towards the end of his life Graves threw out all but a few example essays, along with any notes from his judges that may have existed. It's possible that some of the material is stuffed in a box in an archive somewhere at Union College, but unless and until someone finds it, that doesn't do us much good.

There's no real doubt that the data existed, as a number of people saw it, and Graves published a peer-reviewed paper outlining the theory based on it, and presented additional collated results at some mainstream conferences. But no one analyzed it independently in sufficient detail to verify whether the same theory would emerge for them, either by re-judging the essays or by examining the output of the original judges.

The other possible source of data would be from Spiral Dynamics practitioners, but while I have heard some statistics from such data, I am not aware of any publication of a sufficiently large data set along with the tools and methodology used to produce it in sufficient detail to allow for independent verification.

My point here is not to de-legitimize the science behind E-C theory. It is unverified, not disproven, which is a very significant difference (setting aside the general debate around falsifiability in the social sciences). There is enough information about Graves's methodology (and quite possibly about SD/SDi assessments) to attempt a verification, if anyone had the time and funding for such an enormous project. Which seems unlikely. So instead, I want to consider what space is left open where we simply do not know, and what other outcomes are possible without even requiring Graves (or Beck or Cowan) to be "wrong."

The invisible negative space of E-C theory

If we look at what we do know about how Graves constructed E-C theory and how later assessments have been made, we can then look at the negative space of that knowledge: what we don't know that leaves us a great deal of room for discovery.

What we know: The most relevant points

- 60% of the essays were "nodal", meaning primarily in one level, often with about 50% of an essay's content matching the nodal level, and about 25% each matching the levels behind and ahead

- 40% of the essays were "more mixed"

- Only six of the stages (CP, DQ, ER, FS, A'N', B'O') emerged from the data, while AN and BO were hypothesized and then constructed from reading anthropology research available at the time

- The sequence of levels came from students revising their essays after exposure to more perspectives

- Graves named Gerald Heard's The Five Ages of Man (1963) as one of his theory's three "closest intellectual bedfellows" (NEQ, p. 6), and the narratives of E-C theory and Heard's five ages (directly analogous to BO-FS) show many striking similarities (the other two "bedfellows" are the works of William G. Perry, Jr., and John B. Calhoun)

The point regarding Heard's work deserves more attention than can easily be formatted in a bullet point list. Graves mentions Heard several times in NEQ:

A fourth bit of information passed over or overlooked suggests that the objective-subjective aspect of development is both hierarchical and cyclical. This is left unnoted in most conceptual systems. An outstanding exception is the work of Gerald Heard.

– NEQ p. 36

The work of Gerald Heard and [Lewis] Mumford... supports the thought that we had better give the systems approach to personality and cultural theory a good hard look. Their works are particularly important because they each arrived at five systems in common with E-C theory and in common with each other. They got there from data other than mine. Their data were historical and cultural changes that have taken place over time.

– NEQ p. 448–449

...Mumford accepts that development is open-ended while Heard takes the more traditional Utopian position....

But it is Heard who supports directly the wave-like spiral of systems, for he says:

"... man's history has followed an oscillatory spiral as he

alternates between the exploration of his environment (and the

expansion of his power in it) and investigation of his subjective

being (an attempt to achieve peace with it) but the spiral has

accelerated greatly in the speed of its ascent."

– NEQ pp. 450–451, including a quote from TFAoM, p.284

Graves also noted Heard among those whose conceptions, when he discovered them, provided some language suitable for his conception, which he decided after some consideration to incorporate. (NEQ, p. 134 footnote 64)

Really, I need to finish reading TFAoM and then read Graves's early work from before and after its publication and do an article on the degree to which Heard appears to have influenced Graves's presentation. These brief mentions in NEQ are not enough to make that totally clear, and I do not want to give that influence undue weight. But it appears quite significant, which is all we need for this article.

What we don't know

- What the 40% "more mixed" were like. Presumably some were transitional between adjacent levels, but what more complex mixtures were present? I asked on the Beck-Graves group but did not get any real answers. Perhaps there were contradictory patterns pointing to other paths through the systems that were not clear at the time.

- What were the unclassifiable essays like? It's not clear to me whether they were part of the 40% or if the 60/40 was only within the classifiable essays

- How directly supported by the data are the narrative elements that seem to come from Heard's work? Was it largely present and Graves just aligned some terminology, or did Graves use it as a narrative starting point? A 1962 transcript of a talk by Graves shows a theory that is arguably less recognizable as the E-C theory we know now than than Heard's descriptions would be (TFAoM was published in 1963).

- What additional patterns might emerge if formal grounded theory analysis techniques were applied to the essays. Graves only looked for a "classification of like with like" and gave essentially no other direction. Presumably he analyzed the classified essays to develop the theory, but what might have been flushed out with more recent formal techniques?

- What patterns would emerge from people from a fundamentally intact traditionally collectivistic culture? This is tricky because you have to find cultures that have not yet internalized western ideas or 20th century communism.

- What would emerge from following the same subjects for decades, and looking at the sequences and patterns of change over long periods of time, in environments other than college education or work environments? What about in different cultures with subjects who never encountered Western education or psychology?

- What about people who move to radically different cultures? Do their changes follow the pattern? Do they jump in some way if there is a large gap to cover? Do they downshift if moving to a culture centralized at an earlier stage? If so do they also hold on to their leading-edge level substantially or do they mostly abandon it?

- What would we find if we focused on older adults? Particularly with B'O', did Graves see so little of it because it was that new and rare, or because it mostly appears, for those in whom it appears at all, much later in life? Even looking at many SD applications, the target is often younger to middle-age adults in the workplace. I'm guessing retirees who are content to embrace the unknowable mysteries of the universe don't hire management consultants all that often.

- Would it be possible to construct a consistent methodology that could produce all stages, at least including BO and ideally AN? If so, what would it show about AN vs A'N' and BO vs B'O'? Would more B'O', or any C'P', be detected given significant life condition changes in the last two years?

- Would it be possible to take a more dynamic measurement of how the systems operate in people? The dynamic chords-not-notes aspect is critically important, but while I have seen static-as-of-a-given-moment assessments of the systems in people, I have not seen a real study of the more dynamic behavior. Someone may have done it, in which case I hope to hear about that. But given the question of whether Gravesian theory imposes boundaries on people, being able to do more than hand-wave about the dynamic aspects seems important.

- What happens if we look for personal and cultural developmental sequences that seem exceptionally resistant to framing in Gravesian terms, set aside expectations, and try to build a similar grounded theory process to see what those examples produce?

There is a lot of room to explore

Unfortunately, I'm in no position to set up formal scientific studies of any of the above. But I hope that, as a thought experiment, this demonstrates that what has been reported of Graves's work in NEQ and other sources leaves a lot of room for further exploration of either the scientific or philosophical variety. And while it is possible that further exploration might contradict Graves's work, it is also possible that it might complement it.

It is quite possible that some of this exploration has been done. I hope that this article flushes out any such information, and I will update it with anything I learn. But let's dispense with the idea that because Graves built his theory from data, that the work is done and there is no more to discover. That seems contrary to the spirit in which Graves conducted his research. As he wrote in NEQ, the data frequently surprised him and forced him to throw out expectations and early concepts before he eventually settled on E-C theory as we now know it.

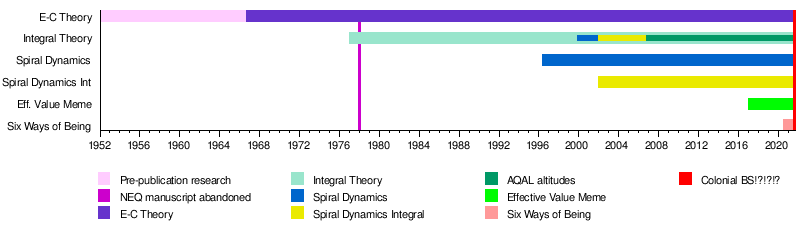

It's been nearly 70 years since Graves started his research. 55 since his first major publication, over 40 since he abandoned the manuscript of NEQ due to ill health. It's been 25 years since Spiral Dynamics was published, nearly 20 since SDi was created, and 15 since "altitudes" of slightly different colors subsumed SDi within Integral Theory. Four years ago, Hanzi published a theory with explicit parallels to Graves in the "cultural code" and "effective value meme" components. Slightly more than a year ago I started soliciting feedback on what I'm now calling the Six Ways of Being. And just under a month ago, Nora Bateson charged that stage theory, as a whole, is BS, and "colonial as hell."

This is an active area of work, as it has been for decades. The jolt of this critique is, in my view, a needed invitation to explore this negative space and consider alternatives, just as Graves was forced by his data decades ago to produce a theory completely unlike anything he had expected. That is not a destructive intent, rather it is a constructive one that may well produce a radically different view. Or it may not. Whatever emerges will be stronger for it.